How Trauma Affects a Child’s Brain

Exposure to trauma is common among children living in out-of-home care, and our team have partnered with numerous providers to deliver trauma-informed support to children and their carers.

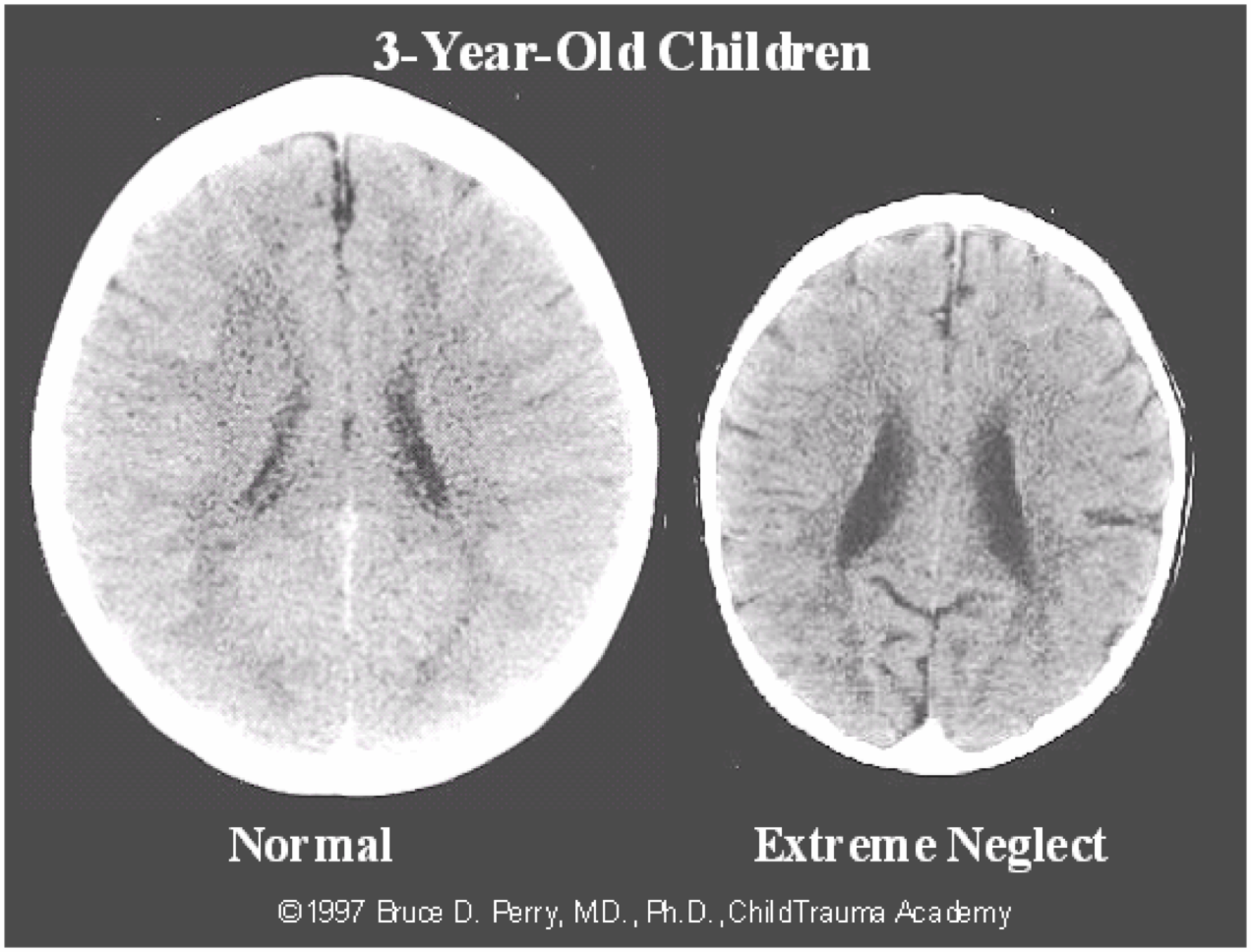

During the first 3 years of life, our brain develops rapidly. Neural connections are made through their sensory experiences and attachments with others. When children experience early adversities such as abuse, neglect, violence and separation, their brain development is physically altered. Early trauma can affect brain areas responsible for regulating emotions, learning, attention, memory, motivation, and more.

Exposure to trauma is common among children living in out-of-home care, and our team at We Care are partnered with numerous out-of-home care providers to deliver trauma-informed support to children and their carers.

The image below highlights the difference in the brains of a healthy child versus a child who has experienced extreme neglect. The brain on the right is significantly smaller than average and has abnormal development of cortical, limbic and midbrain structures, which we will discuss below.

How the brain develops

To understand how trauma affects the brain, it’s important to look at how the brain develops. Our brain develops from the ‘bottom-up,’ meaning our brainstem (responsible for survival functions such as breathing) is developed first, then our limbic system (responsible for emotions), and lastly our cortex (responsible for learning and problem solving, which does not fully develop until adulthood).

.jpeg?width=1966&name=5831_WeCare_COVID-19_Social-Post_brain_V1-0-05%20(1).jpeg) Image: Adapted from Dr Bruce Perry’s Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (2006).

Image: Adapted from Dr Bruce Perry’s Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (2006).

When we are triggered by fear or stress, our body releases hormones such as cortisol and we enter a state of fight/flight/or freeze. When we are in this state, our survival brain (brainstem) takes over and ‘turns off’ other areas of the brain that enable us to be calm, learn, think and respond flexibly. You may have noticed this when your child is having a meltdown and it is impossible to reason with them in the moment. It is not until we calm our brainstem, that we can develop and access higher parts of our brain.

For babies, a recurring state of fight/flight/or freeze (e.g. prolonged crying, inconsistent responses) programs the brain to develop lots of connections to the survival part of the brain and slows down the development of brain regions responsible for regulating emotions and learning. As children grow older, they are triggered into a state of survival far more easily and more frequently than children who have not experienced trauma, due to the increased connections in the survival part of the brain.

So how do we help children who have been exposed to trauma in their early years?

Now that we know our brain changes and adapts to our environment, the promising news is that it can form new connections and pathways over time when positive changes are made to our environment. It just means it will take more time than it would for a typically developing child without trauma and require patience and consistency from caregivers and professionals.

An important aspect of supporting a child who has experienced trauma means learning to recognise which part of their brain is activated and responding accordingly. We cannot fully access the thinking and learning part of our brain unless the other regions are calm. Whilst healing from trauma can be a complex and lengthy process, the following strategies are suggested for calming a child’s survival and emotional centres of the brain so that they can engage their cortex to learn, problem-solve, control emotions, consider future consequences, focus attention and control behaviour.

Part of Brain Activated: Brainstem (safety and survival)

What it may look like:

- Anxiety, sleep issues, impulsive behaviour, sensory processing issues, state of fight/flight/or freeze.

Strategies to calm the brainstem:

- The most important thing for any child, particularly those who are healing from trauma, is the presence of a stable caregiver who can provide consistent, responsive, unconditional love and attention.

- Provide predictability to your child’s day. Knowing what is happening helps children feel in control, safe and secure. This does not mean routines are controlling, just that children need support to anticipate what is happening.

- Rhythmic patterns and movement such as rocking, swinging, throwing a ball, singing, listening to music and exercise all help to calm the brain.

An important point to consider:

All children develop at different rates, so it is important that we don’t set timeframes for this. There is no determined time frame in which we can expect to see improvements when we provide the strategies above. For some kids, it may take years and for others just months.

Part of Brain Activated: Limbic (emotions)

What it may look like:

- Heightened emotions (anger, fear, sadness, enjoyment), deadened emotions (numbness), oppositional behaviour, clingy, running away, hiding.

Strategies to calm the emotion part of the brain:

- Helping children name their emotions

- Connecting with your child by validating their emotion, e.g. “You’re really mad that your friend took the pencils you were using” or “I can see you are feeling…”.

- Cultural validation and restoration

- Building self-esteem

Part of Brain Activated: Cortex (thinking and learning)

What it may look like:

- Memory issues, difficulty organising, planning and problem solving, self-esteem issues, flashbacks.

Strategies to engage the cortex:

- Once you’ve helped your child to connect to their emotions, help them use their thinking brain to address the problem. For example: “What could you say to the other child to ask for your toy back?” or “What are some things you can do to make yourself feel better when you are sad…?”

- Make learning hands-on as much as possible. For e.g using rocks outside to teach adding and subtracting. Incorporating problem-solving tasks in make-believe games/role plays.

- Make information visible (notes, cards, lists, visuals) to assist with memory. The need for memory aids can be decreased over time as working memory improves.

For caregivers who would like to learn more about how to connect with their children to positively influence their behaviour and learning, you can make an appointment to see one of our experienced psychologists by contacting our office on 02 4013 6079 or completing our referral form.

We Care are also running the Circle of Security Parenting Program, which is a relationship/attachment focused program that looks at how caregivers can support their children to build secure relationships. For more information about the Circle of Security and how you can be involved, click here.

Written by

Rebecca Tattoli

Psychologist